The Search for Jennie Newcomb’s Maiden Name

Jennie Van Rees Newcomb: 1873-1957

The lurid stories on Nathaniel Newcomb’s apparent bigamous

marriage neglected to provide a critical piece of information: the maiden name

and background of Nathaniel’s humiliated second “wife” Jennie. I set out to track it down and find out what

happened to her.

New York marriage records are ridiculously difficult to uncover, so I had

no luck trying to find Nathaniel Newcomb and Jennie Newcomb’s marriage license.

There was even some confusion as to which state and city they chose for their marriage ceremony,

and then there is the question of whether it was legal at all given his failure to

get a divorce from his first wife. Did they bother to actually marry at all? Anything

is possible, although they presented themselves to the world as husband and

wife for several years.

Following Nathaniel’s death in 1903, Jennie Newcomb seemed

to disappear. Her brother-in-law implied she came from a well-to-do Brooklyn

family, but to preserve her privacy, he wouldn’t give her last name. He said

she was returning home to Brooklyn after closing up Nathaniel’s New Jersey

home. I searched Brooklyn records for her following the scandal, but found

nothing.

To my surprise, I found her in the New Jersey state census

in 1905, just two years after her husband’s death. She had stated on previous

census records that her parents were born in Holland, so when I found her

living with a Marie Bross, also from Holland, I thought she had to be a family

member. Marie was a year younger than Jennie, and was married with a young son

named Harold. Marie’s husband was also named Harold Bross. It seemed likely

Marie was Jennie’s sister. I searched for Marie’s marriage records to find the

women’s maiden name, but was unsuccessful.

I then turned to Newspapers.com, thinking Marie’s obituary

might reveal her maiden name. Instead my search turned up an obituary for a

Cornelius Van Rees, a successful publisher and Dutch immigrant. One of his

surviving sisters was Marie Bross. Aha! Perhaps Jennie’s maiden name was Van

Rees.

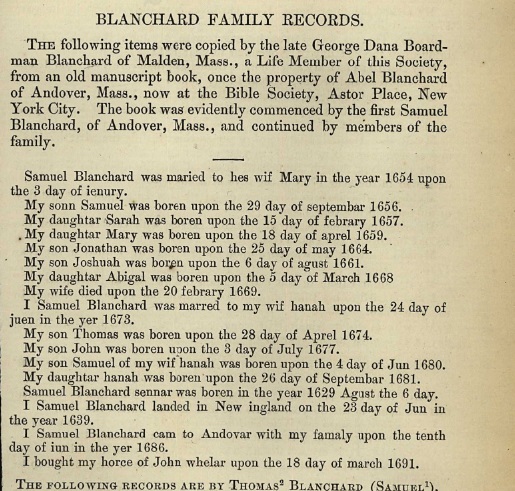

I searched Ancestry records under that name in Brooklyn, and

turned up a New York State Census Record for 1892, listing the entire van Rees

family:

Father Richard, a carpenter, age 65, wife Jennie, age 60,

four sons, Abram, Cornelius, Peter and Richard, ages 30, 23, 22 and 14 (all

mentioned in Cornelius’ obit), and

daughters Minnie, 26, Fannie, 28, and Jennie, 18. Jennie, like her sisters, was

working as a sales lady in a store. Marie must have already been married and

out of the house.

Jennie must have met Nathaniel Newcomb just a year or so

after the census, for they were married two years later in 1894 when Jennie was

only 20 and Nathaniel was 46. They apparently lived a fairly lavish life. Here

is what the newspaper reported after Nathaniel’s death:

“While Newcomb lived he was known as the prosperous president

of the Manhattan Steamship Company, the husband of a woman of wealth and high

social connections and the possessor of a beautiful residence and fine stable

of horses at Westfield, N.J., where he made his home.”

The truth of the matter was that Nathaniel was lower class,

as was Jennie. They re-invented themselves following the marriage—they were

social climbers. Nathaniel’s brother Francis fed the newspapers with false

information that continued the fiction that they both came from wealth.

After Nathaniel’s death, his first wife Sarah and her attorney

attempted to claim all of Nathaniel’s property. In addition, there were other

creditors—Nathaniel apparently had extensive debts. Jennie apparently grabbed

what she could of their possessions before the other claimants could. The

newspaper reported that following the appearance of wife Sarah, “the blue

ribbon horses, all the valuable furniture and Mr. Newcomb’s jewelry and cash

departed from Westfield, as did Mrs. Newcomb No. 2.”

The article goes on to address the issue of the steamship

company shares and the various counterclaims for ownership of the company

assets, and then also notes, “Meanwhile all concerned are seeking to discover

the whereabouts of considerable sums in cash known to have been in possession

of Newcomb just previous to his death.”

The articles seems to imply that Jennie made off with all

the money and valuables, but given that she was forced to move in with her

married sister in lower class Cranford/Passaic, I rather doubt she got much of

value from her dead husband’s estate.

But where did she go after 1905? There was no Jennie van

Rees or Jennie Newcomb in the 1910 census, either with her sister’s family or

on her own. Had she remarried? I examined Cornelius’ obituary more closely, and

realized that one sister was identified only by her husband’s name, a Mrs.

Jacob Van Reen. Could this be Jennie? A little searching confirmed my

suspicion.

Jennie met a Dutch businessman in Passaic, Jacob Van Reen.

Jacob was just a year or so older than Jennie and was a wholesale dry goods

merchant. They seem to have married around 1907, for his 1947 obituary states

that he and Jennie had been married for forty years. They remained in the

Passaic area until his death. They had no children, and Jennie's name does not appear

in any newspaper articles, and her husband only occasionally pops up as a member of various

charitable groups.

|

| 392 Lafayette Ave., Passaic today |

Census records show that they lived at 392 Lafayette Avenue

in 1920, and moved to 72 Belmont Place by 1930. The Lafayette Ave. house, built

in 1900, was quite large—over 3400 square feet. The Belmont property was

considerably smaller, under 2000 square feet. The family does not appear to have been wealthy, but were just comfortably middle class. Jennie’s sister Marie apparently

left her husband before 1920, and she and her son Harold moved in with Jennie and

her husband, living with them for over a decade. Harold returned to Jennie's home in the 1940s and 1950s, perhaps to help care for his aunt and uncle as they aged.

Jennie died December 19, 1957. She was buried on Staten Island.

Interestingly, she left her estate to Harold Bross, her sister Marie’s son.

However, Harold was identified in estate documents and Jennie's obituary as Jennie’s son. I am not sure

if she adopted Harold at some point, or if this was a sort of honorary

relationship in recognition of Jennie taking him in while he was young. Another

interesting mystery in a fascinating life. At least now Jennie can be properly

identified on my family tree, and on Ancestry.