Catharine Bolinger Funk: 1837-1871

Discovering a Tragic Early Marriage Helps to Chip Away at a Brick Wall

For many

years, my maternal second great-grandmother Catharine Funk was a brick wall in

my family tree. I had few records for either Catherine or her husband, Charles

Funk, and few clues to help me find out where these two people had come from. I

had no birth record for Catharine, and no death record. She just mysteriously

disappeared from the records after 1870, along with her three oldest children.

I found no burial records for any of them. So who was Catharine? And what

happened to her?

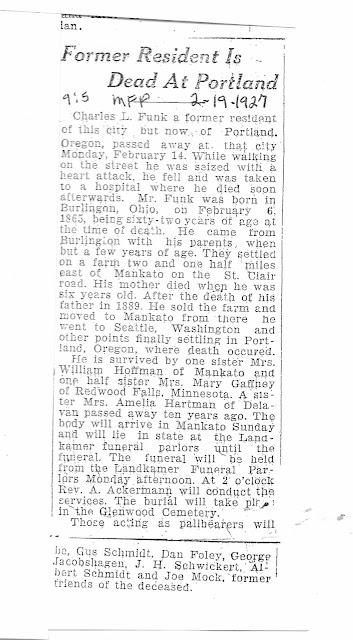

My first

real clue came from a research trip to the Blue Earth County Historical

Society—the last records for Catharine found her living on a farm outside

Mankato, Minnesota, the county seat of Blue Earth County. While searching old

newspaper records at the Historical Society for any Funk family members, I

found the obituary for Catharine’s second son, Charles Funk. The obituary gave

me two critical pieces of information:

1. The obituary stated, “His mother died when he

was six years old.” Since Charles was born on February 6, 1865, that meant his

mother likely died in 1871.

2. The obituary stated that he was survived by one

sister, Mrs. William Hoffman of Mankato (my great-grandmother) “and one

half-sister, Mrs. Mary Gaffney of Redwood Falls.” This was the first hint that

my second great-grandfather, Charles Funk, was not the father of all six of

Catharine’s children. On census records, the three oldest children were just

listed by first name, so were assumed by census transcribers to share the Funk

surname. Perhaps Mary and her older siblings William and Sophia went by a

different surname, which would explain why I had been unable to find any trace

of them after 1870.

So my first job was to find out Mary Gaffney’s maiden name, which would tell me what Catharine’s previous husband’s name had been. I quickly found her marriage record: George Gaffney married Mary L. Grentz on January 14, 1879.

I immediately sought marriage records for a Catharine Grentz and anyone with a surname of Funk, in Iowa, since Mary Grentz Gaffney was born in Iowa. Bingo! The Iowa Select Marriages Index listed a C. N. Funk marrying Catharine Grentz on November 21, 1863 in Mahaska County, Iowa.

I also found an 1860 census record that included

Catharine and her two oldest children, William and Sophia, along with her

husband Louis Grentz. Louis was listed as a brewer, and the family was living

in the city of Oskaloosa, located in Mahaska County, Iowa. Louis was born in

Darmstadt, Germany, and Catharine was born in Ohio.

I could find no records of Louis and Catharine’s marriage in Iowa, so I tried Ohio. I found a Lewis Grantz marrying Catharine Bollinger in Delaware County, Ohio on May 11, 1856. At long last I had a maiden name for Catharine! She was a Bollinger!

|

| Marriage record for Lewis Grantz and Catharine Bollinger |

I found Catharine’s parents and siblings on the 1850 federal census, living in the town of Delaware in Delaware County, Ohio. Jacob and Catharine Bolinger (with only one “L”) had five children at the time, Catharine being the oldest daughter. The couple went on to have three more children, so Catharine was the second oldest of their eight children. Two of Catherine’s children were named for her siblings William Bolinger and Mary Bolinger Ryan.

Many of the bricks in my Catherine

Funk brick wall had been removed: I had a tentative death date and I had found

her parents. But there was still a mystery: what happened to Catharine’s first

husband, Lewis/Louis Grentz/Grantz? He was living with the family in 1860, but

by 1863, Catharine was free to marry Charles Funk. What happened in those three

intervening years?

A search of Newspapers.com provided

the tragic answer. According to the Oskaloosa Herald, Lewis Grentz was in

business with a friend, running a brewery in Oskaloosa called Blatner and

Grantz. (Note: the newspaper spelled

both surnames incorrectly. Grantz should be Grentz, and Blatner should be

Blattner.) He apparently suffered from mental illness and committed suicide on

November 2, 1861, “first gashing himself in the stomach with a butcher knife

and then drowning himself in the Muchikinock.” The Muchikinock was a creek that

ran through Oskaloosa. Now it is more marsh than creek; drowning would be

nearly impossible. However, in late fall of 1861, the Muchikinock was probably

a much larger, faster- moving body of water.

The article went on to note that

Lewis “had been unwell for a week, some of the time deranged, but it was not

known that he contemplated suicide.” In those days, there really wasn’t any

appropriate treatment for mental illness other than committing the patient to

an asylum. Poor Catharine! She must have been so desperate when her husband

suffered some sort of mental breakdown. She would have had few options for

helping him.

And then to be left a widow in her twenties with three small children, which would be difficult enough without the added shame that accompanied suicide in the nineteenth century. Hopefully Lewis’ partner, C. Blattner, helped her with money. The brewery survived for several more years with a new partner, David Newbrand, so must have been a successful business.

|

| Lewis Grentz' partner, Blattner, made a success of the brewery with a new partner. 1870s. |

|

| 1860 Federal Census for Oskaloosa IA showing Charles Nicolas Funk |

Shortly after their marriage,

Charles and Catharine relocated to a farm near Mankato, Minnesota, and Charles

became a farmer, eventually abandoning his cabinetmaking business. The couple

had three children together, including my great-grandmother Lena Funk, Amelia

Funk and Charles Funk.

It took me a couple years to chip

away at the Catharine Funk “brick wall”, but thanks to two newspaper obituary

items—Catherine’s son Charles Funk’s, and her first husband Lewis Grentz’s--I

was able to discover Catharine’s parentage and her fate. I also discovered how

difficult and tragic her life had been as a young mother in the 1860s. I hope

that further research will give me insight into the lives of her parents, her

siblings, and the fate of her two oldest children.

Sources:

Marriage and census records from Ancestry.com.

Newspaper articles from Newspaper.com