Young Mills Daughter Loses Both Parents and Brother in Single Year

Gehial

Hiram Mills: 1833-1863 (Maternal Second Great-Granduncle)

Helen

Egleston: 1839-1863 (Maternal Second Great-Grandaunt by Marriage)

Gehial

Mills Jr.: 1863-1863 (Maternal First Cousin 3x Removed)

Hannah Amy

Mills: 1856-1945 (Maternal First Cousin 3x Removed)

Orrin

Oliver Mills (see previous post) was not the only Mills son to serve in the

Civil War. His older brother, Gehial Hiram Mills, usually known as Hiram Mills,

also served in the Union Army. However, unlike Orrin, Hiram did not survive the

war. He was sent home wounded but never recovered, dying in Wisconsin in September

1863. However, Hiram was not the only member of his family to die that year.

His wife and infant son also died in 1863, leaving his young daughter, Hannah

Amy Mills, an orphan. She was the end of her father’s line.

Gehial

Hiram Mills was born October 29, 1833 in St. Lawrence County, New York, to

parents Joel Mills and Orpha Pratt Mills. He was the third of their five

children. The family moved to Wisconsin in the 1840s, and that’s where Hiram

met his wife, Helen (often recorded as Hellen) Egleston. The couple married

November 4, 1855; Hiram was 22 and Helen was only sixteen. Their first child, a

daughter named Hannah Amy, was born a year later on December 26, 1856.

By 1860, Hiram was farming near Marcellon, Columbia County, Wisconsin. The census record indicates he was renting a farm, as the census form shows no value in the real property column.

Perhaps that was why, a year later, he enlisted in the Portage

Light Guard, a cavalry unit that was formed in the area near Hiram’s farm

(Marcellon was ten miles from the town of Portage). Soldiers often received or

were promised bounty money for signing up, ranging from $20 to $60, which was a

considerable amount in that era. Hiram may have dreamed of using his military

pay to buy farmland of his own.

Hiram’s

name appears in the unit roster in the Wisconsin State Register on April 27,

1861. The article also notes that the Light Guard was “accepted by the Governor

for the second regiment of the Wisconsin Militia.” A full roster of Wisconsin

volunteers lists Hiram as a “wagoner”, which was a soldier who drove a wagon

that carried supplies or regimental baggage. The wagoner was responsible for

the draft animals—usually a team of four horses or six mules—and the wagon

itself.

|

| Hiram Mills at time of Civil War |

With Hiram

gone to war, and the farm likely rented to someone new, what happened to

Hiram’s wife and daughter? I believe they moved in with Helen’s parents, Benjamin

and Hannah Egleston, who lived nearby in Columbia County near Pardeeville.

|

| 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry regimental flag |

The Second

Wisconsin Cavalry finished training and organizing in Milwaukee in March 1862

and were sent to St. Louis March 24. Hiram probably had at least one furlough

home before being shipped out, because Helen Mills became pregnant, delivering

a son either late in 1862 or in early January 1863. Tragically, she died

shortly after the birth on January 7, 1863, leaving her two young children in

her parents’ care.

Hiram’s

regiment served in Missouri and Arkansas until January 1863 when they were

moved to Memphis, Tennessee. By June, they had pushed south to Vicksburg, and

then were assigned to General Sherman’s Jackson campaign in July.

|

| Hiram Mills headstone at Pardeeville Cemetery |

At some

point during 1863, Hiram was injured and became seriously ill, for he was furloughed

in August 1863 and sent home to Wisconsin. By the time he arrived in Wisconsin,

his young wife was already dead. Her parents must have cared for her little

son, Gehial Jr., very well, for he had survived nearly eight months, long

enough for his father to meet him. Little Gehial Jr. died September 4, 1863,

and his father, Gehial Hiram Mills, died in Pardeeville just six days later on

September 10, 1863. Helen was 24 and Hiram was only 29 at death. Their

remaining child, Hannah Amy Mills, was only six years old when she was

orphaned. Hiram, Helen and Gehial Jr. were all buried in the Pardeeville Cemetery,

but only Hiram’s gravestone has been photographed.

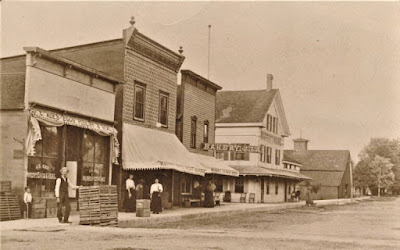

|

| Pardeeville, Wisconsin during the 1800s |

Some

family trees claimed Hiram died from war wounds. However, I discovered that Hiram

wasn’t listed among the Second Wisconsin Cavalry’s war casualties, so his unit

commanders didn’t treat his injury as a battle wound. The only regiment records

I found merely stated that Hiram died in Pardeeville, Wisconsin.

I would

have been left in the dark about Hiram’s true cause of death if I hadn’t

discovered his pension file—35 fascinating pages that recount how his daughter’s

guardian, her grandmother Hannah Egleston, fought to receive a dependent’s pension

for Hannah Amy. Her initial application stated that Hiram died of illness

contracted in war, which led the pension department to initially deny the

application—a disease could have been unrelated to Hiram’s service, after all.

However, Hannah Egleston persisted, explaining that Hiram’s illness was caused

by an injury he received while on duty. She contacted officers and soldiers

from his regiment, begging for affidavits that would support the pension

application.

Part of Hannah Egleston's pension application on behalf of her granddaughter

The army

demanded that she provide an affidavit from a commissioned officer in Hiram’s

unit. This turned out to be impossible. Hannah submitted a new affidavit stating

that she was not able to provide proof of Hiram’s injury from his cavalry

unit’s officers because “at the time of the said injury said Mills was on a

scout under the command of Sergeant Hewitt and no commissioned officers was

present and knowing to this said hurt…”

However, she

did obtain the affidavit of two other regiment members, George Hewitt (presumably

the sergeant leading the scouting party) and George W. Ames, who stated that

they were also in the Second Wisconsin Cavalry, knew Hiram and “in the line of his duty as a soldier near

Helena Arkansas the said Mills was thrown by his horse rearing and falling over

backwards and on to him and his left-side badly injured so that from that time

till the next August when he was…furloughed he did but little duty, was a great

deal of the time in hospital and continually complaining of the injury to his

side.”

Obviously

from his comrades’ description, Hiram was no longer a wagoner by 1863, but was

a regular cavalry soldier, riding on scouting parties and participating in

battles. The injury sounds horrific—I can imagine the horror as the huge horse

fell on top of Hiram.

The doctor

who attended Hiram in Wisconsin, Orin D. Coleman, testified that he was called

to the Egleston house to help Hiram on August 25, 1863 and “found him very sick

with inflammation of the bowels (peritonitis)” and that he continued to attend

to Hiram until his death. He reported that he read the affidavit supplied by

Hiram’s cavalry comrades about the injury Hiram sustained and “that such an

injury…might have been and probably was the precipitary (I think that is the

word—hard to read) cause of the inflammation of which he died.”

Poor

Hiram. He must have suffered some sort of internal crush injury that left him

with an intestinal rupture and infection. The pain must have been agonizing.

How did he manage to get back home from Arkansas in such a state? And how did

he manage to survive for nearly three weeks after he made it home?

The

additional affidavits were apparently persuasive, for on September 11, 1866 the

army approved the pension application. Hannah Amy received a pension in the

amount of $8 per month back-dated to the date of her father’s death, and

continuing until December 28, 1873. I’m sure this money must have been a

godsend to Hannah Amy’s grandparents.

.jpg) |

| Pension approval record |

As Hiram’s

daughter grew up, she went by her middle name of Amy. She was still living with

her grandparents at the time of the 1870 census, along with their two youngest

children. Her grandmother and guardian died a few years later. There are no

further records of Amy until she appears on the 1880 census in Meeker County,

Minnesota, married to Harry Porter. The census form records that they had

married in 1880. By the end of that year, they were parents.

|

| Amy Mills Porter, husband Harry, and three of their children. |

Amy and

Harry went on to have six children. Following Harry’s death in 1895, Amy

supported her children first as a seamstress, and then by the 1910 census, Amy

was operating a restaurant in Sanborn, North Dakota, and her three youngest daughters

were teaching and working as telephone operators. She ended up moving to

Washington state, and died September 1, 1945. She was eighty-eight years old.

Amy Mills

may have been the end of Gehial Hiram Mills’ line, but her children and

grandchildren carried on the Mills family legacy into the future.

Sources:

Wisconsin

Volunteers: War of the Rebellion 1861-1865. Arranged Alphabetically. Compiled

under the direction of the Adjutants General, published by the State of

Wisconsin, Democrat Printing Company. 1914. https://content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection/tp/id/36915/rec/3

US, Civil

War "Widows' Pensions", 1861-1910. National Archives. Case Files of

Approved Pension Applications of Widows and Other Veterans of the Army and Navy

Who Served Mainly in the Civil War and the War With Spain, compiled 1861 – 1934.

Record group 15. https://www.fold3.com/file/280249850/mills-hiram-us-civil-war-widows-pensions-1861-1910?terms=mills,war,us,civil,hiram

FindaGrave

entries for Gehial Hiram Mills, Helen Egleston Mills, and Gehial Mills, Jr. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/45710095/gehial-hiram-mills?_gl=1*192jxs4*_gcl_au*MTg1NTA3NTEwOC4xNzE1MDM0MzIy*_ga*OTczMjY1MzMyLjE3MDQ4NTI3MzQ.*_ga_4QT8FMEX30*ZDc1MjVjMWMtYmU3MC00ZjUyLTg1NDUtNmFmZGRiY2NkYzkzLjI0NS4xLjE3MjAxMjIzMDguNDkuMC4w*_ga_LMK6K2LSJH*ZDc1MjVjMWMtYmU3MC00ZjUyLTg1NDUtNmFmZGRiY2NkYzkzLjI0Ni4xLjE3MjAxMjIzMDguMC4wLjA.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2nd_Wisconsin_Cavalry_Regiment

Wisconsin

Veterans Museum: 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry. Photo of Standard, 2nd

Wisconsin Cavalry V1964 219 7. https://wisvetsmuseum.com/2nd-wisconsin-cavalry/